The Restorative Power of “The Interesting”

This is a part of a series of reflections, on occasional Sundays, from Next Big Idea co-founder Rufus Griscom about his experience hosting the weekly NBI podcast.

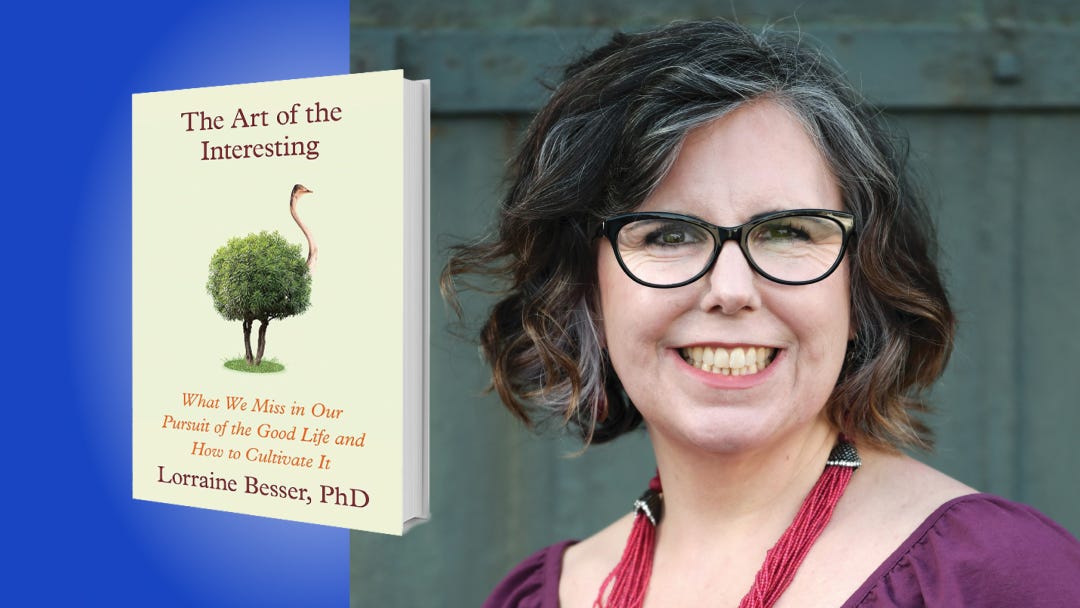

Listen to his most recent conversation with philosopher Lorraine Besser about “The Art of the Interesting” on Apple and Spotify.

Before I get started today, two notes:

First, my colleague Caleb Bissinger just had a beautiful conversation with Ann Wroe, who has written obituaries for the Economist for two decades, a practice she calls “catching souls.” What can the dead teach us about living? Listen on Apple or Spotify.

Second, on a recent team retreat, my colleague Michael Kovnat, Next Big Idea co-founder and regular writer of this newsletter, proposed Live Brighter as a tagline for the Next Big Idea. It’s grown on me. What do you think?

It gets to the heart of what we aim to do here at NBIC — bring you a selection of new ideas every week that provide you with illuminating insights, in both senses of the word: insights that help you live smarter, and make the world a little brighter.

If you know others who would like to join our exploration of brighter living, please share this email. Better still, it’s the best time of the year to give friends, family and colleagues NBIC as a gift, with 50% of our digital memberships using code Holiday50, and 30% off box subscriptions using code Holiday30. Thank you, from our family to yours, for helping us spread the word.

I don’t know whether the results of the presidential election put a bounce in your step, or gutted you, left you feeling angry at the world. There are people I care about in both camps.

For me, the outcome was humbling. The world, it seems, resists my attempts to control it. But there is a silver lining. Even when the world is upside down, it remains fascinating. In fact, it’s almost more interesting when it’s not behaving the way that I think it should.

Taking an interest in the world, in this sense, provides a kind of insurance policy. When it’s good, it’s good. And when it’s bad, it’s interesting.

This outlook has helped me navigate my life with a certain buoyancy. Other people call it optimism, but that’s now how I see it — I try to be balanced in my assessment of likely future outcomes. I like to think of this outlook as a kind of enchanted realism. When it’s good, it’s good; when it’s bad, it’s interesting.

I have always thought of this as part of an artistic sensibility. Just as good day traders have figured out how to make money when the market is going down, artists know how to turn pain into beauty, discomfort into intrigue. The option to shift into this mindset at any time is empowering.

You can imagine my surprise at discovering that Middlebury philosophy professor Lorraine Besser just wrote a book making precisely this case. It’s called The Art of the Interesting: What We Miss In Our Pursuit of the Good Life, and How to Cultivate It.

For thousands of years, philosophers have been arguing about “the good life” — what it looks like, how to live it. They have tended to focus on our pursuit of happiness, and our pursuit of meaning. Lorraine says they are missing a critical third leg of the stool – The Interesting.

Does any of the following strike you as interesting?

Lemons float, but limes sink.

Before becoming an actor, Christopher Walken was a lion tamer in the circus.

The circulatory system of a human being is more than 60,000 miles long.

Steve Martin was a philosophy major.

Tiger shark embryos start attacking each other while in their mother's womb.

Actor Daniel Radcliffe broke more than 80 wands while filming the Harry Potter movies.

How about experiences? Running in the rain? Talking to strangers? If none of that hits, you may need an intervention from Lorraine.

As much as I love the curious, appreciative-of-the-interesting mindset, I have come to the conclusion that there is no such thing as a single optimal psychological state. For millennia people have posited an ideal mental state to which we should aspire. For Buddhists it was Zen or Satori, a state of enlightenment or awakening; for meditators it is mindfulness, a state of present-moment awareness; for Aristotle it was Eudaimonia, an engagement in reason and virtue; for Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi it was Flow, a state of complete absorption in a task; for Teddy Roosevelt, it was the high adrenaline engagement of the man “in the arena.” None of these states, however, are sustainable for long periods of time.

In my experience, the good life consists of a cycle of states — periods of observation, in which we appreciate “the interesting”; periods of playful exploration with others; periods of exhilarating high-engagement flow state in which we build things of value, ideally with others; and then rest. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Lorraine, I know, agrees with this view that “the interesting” is one piece — a critical piece, she would say — of the cycle of mental states that characterizes the good life.

What do you think? Let’s discuss. Listen on Apple or Spotify, and join the discussion below.

Here's another case for appreciating the interesting — we learn better when we can occupy a curious, disinterested state. Jonathan Haidt, with whom we had a great conversation recently, makes the case in The Righteous Mind that most of us have a tendency to use reason to justify opinions that we form based on group allegiances and emotional intuition. If we want to bust out of that, and actually have real conversations, we need to spend time simply ... being interested.

Novelty is spice of life , as they say.