What Could Possibly Go Right? Reid Hoffman on Our AI Future

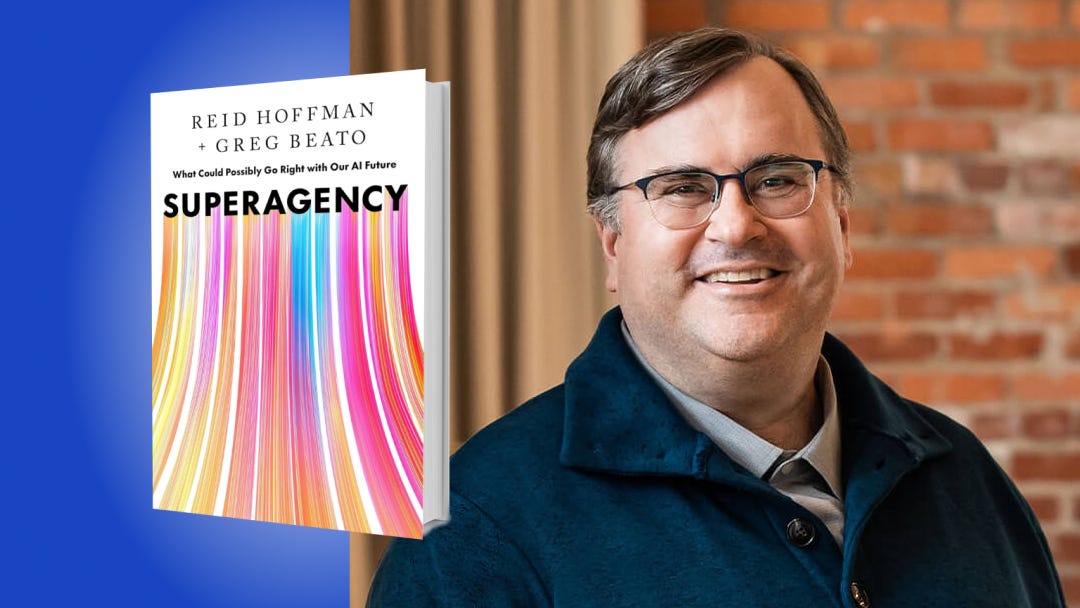

The LinkedIn co-founder shares an exclusive excerpt from Superagency: What Could Possibly Go Right with Our AI Future

We have something special for you today — an exclusive excerpt from the brand-new book, released today, Superagency: What Could Possibly Go Right with Our AI Future, co-written by legendary tech entrepreneur Reid Hoffman. Reid is not only the co-founder of LinkedIn, an early investor in OpenAI, and a board member at Microsoft, he is also the author of 6 books including The Startup of You and Blitzscaling. In Superagency, he and his co-author, technology journalist Greg Beato, make the bold case that artificial intelligence need not rob us of our autonomy or sense of purpose. Instead, Hoffman argues, it can become a powerful tool for broadening human agency and reshaping our shared future.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Reid on Friday for the Next Big Idea podcast (Apple Podcasts | Spotify), which will drop this Thursday. Reid struck me as deeply thoughtful and kind, one of the good guys. Though I alternate between excitement about AI’s enormous near- to medium-term potential to solve humanity’s problems, and concern about its long term dangers, I was buoyed by Reid’s optimism. As Reid put it in our conversation, “I believe very strongly that [because of AI] there is this very positive human future [with] superagency [and] superpowers for humanity, for a very broad swath of human beings — and hopefully, ultimately all.” Refreshing, right?

What follows is the introduction to Superagency. You will also find below a video excerpt from our conversation.

- Rufus Griscom

Introduction:

Throughout history, new technologies have regularly sparked visions of impending dehumanization and societal collapse. The printing press, the power loom, the telephone, the camera, and the automobile all faced significant skepticism and sometimes even violent opposition on their way to becoming mainstays of modern living.

Fifteenth-century doom-mongers argued that the printing press would dramatically destabilize society by enabling heresy and misinformation, and by undermining the authority of the clergy and scholars. The telephone was characterized as a device that could displace the intimacy of in-person visits and also make friends too transparent to one another. In the early decades of the car's ascent, critics claimed it was destroying family life, with unmarried men choosing to save up for Model Ts instead of getting married and having kids, and married men resorting to divorce to escape the pressures of consumption that cars helped create.

This same kind of doom and gloom was applied to society-wide automation in the 1950s, when increasingly sophisticated machines were dramatically impacting factories and office buildings alike, with everyone from bakers, meatcutters, autoworkers, and U.S. Census Bureau statisticians seeing their overall numbers dwindle. In 1961, Time magazine reported that labor experts believed that without intervention from business interests, unions, and the government, automation would continue to grow the "permanently unemployed." By the mid-1960s, congressional subcommittees were regularly holding hearings regarding the mainframe computer's potential threat to privacy, free will, and the average citizen's capacity to make a life of their own choosing.

Today, U.S. unemployment rates are lower than they were in 1961. The average U.S. citizen lives in a world where PCs, the internet, and smartphones have ushered in a new age of individualism and self-determination rather than crushing authoritarian compliance or the end of humanity. But with the emergence and ongoing evolution of highly capable AIs, it's not just that familiar fears about technology persist; they're growing.

Even among AI developers, some believe that future instances of superintelligent AIs could represent an extinction-level threat to humanity. Others point out that, at the very least, humans acting with malicious intent will be able to use AIs to create catastrophic damage well before the machines themselves wage unilateral war against humanity. Additional concerns include massive job displacement, total human obsolescence, and a world where a tiny cabal of techno-elites capture whatever benefits, if any, AI enables.

The doomsday warnings are different this time, these observers insist, because the technology itself is different this time. AI can already simulate core aspects of human intelligence. Many researchers believe it will soon attain the capacity to act with complete and extremely capable autonomy, in ways that aren't aligned with human values or intentions.

Robots and other kinds of highly intelligent systems have long existed in sci-fi novels, comic books, and movies as our dark doppelgangers and adversaries. So as today's state-of-the-art AIs hold forth like benevolent but coolly rational grad students, it's only natural to see foreshadowing of HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, or the Borg from Star Trek, or, in a less self-aware and more overtly menacing form, The Terminator's relentless killer robot. These narratives have shaped our worst visions of the future for a long, long time.

But are they the right narratives? The future is notoriously hard to foresee accurately—for pessimists and optimists alike. We didn't get the permanent mass unemployment that labor experts in the early 1960s anticipated; nor did we get The Jetsons and its flying cars—at least not yet.

As hard as it may be to accurately predict the future, it's even harder to stop it. The world keeps changing. Simply trying to stop history by entrenching the status quo —through prohibitions, pauses, and other efforts to micro-manage who gets to do what—is not going to help us humans meet either the challenges or the opportunities that AI presents.

That's because as much as collaboration defines us, competition does too. We form groups of all kinds, at all levels, to amplify our efforts, often deploying our collective power against other teams, other companies, other countries. Even within our own groups of like-minded allies, competition emerges, because of variations in values and goals. And each group and subgroup is generally adept at rationalizing self-interest in the name of the greater good.

Coordinating at a group level to ban, constrain, or even just contain a new technology is hard. Doing so at a state or national level is even harder. Coordinating globally is like herding cats—if cats were armed, tribal, and had different languages, different gods, and dreams for the future that went beyond their next meal.

Meanwhile, the more powerful the technology, the harder the coordination problem, and that means you'll never get the future you want simply by prohibiting the future you don't want. Refusing to actively shape the future never works, and that's especially true now that the other side of the world is only just a few clicks away. Other actors have other futures in mind.

What should we do? Fundamentally, the surest way to prevent a bad future is to steer toward a better one that, by its existence, makes significantly worse outcomes harder to achieve.

At this point we know from thousands of years of experience that if a technology can be created, humans will create it. As I've written elsewhere, including in my previous book, Impromptu, we're Homo techne at least as much as we're Homo sapiens. We continuously create new tools to amplify our capabilities and shape the world to our liking. In turn, these tools end up shaping us as well. What this suggests is that humanism and technology, so often presented as oppositional forces, are in fact integrative ones. Every new technology we've invented‚ from language, to books, to the mobile phone‚ has defined, redefined, deepened, and expanded what it means to be human.

We're the initiators of this process, but we can't fully control it. Once set in motion, new technologies exert a gravity of their own: a world where steam power exists works differently than the world that preceded it. This is precisely why prohibition or constraint alone is never enough: they offer stasis and resistance at the very moment we should be pushing forward in pursuit of the brightest possible future.

Reid describes the cascade of innovations likely to come in the next 5 to 10 years:

Some might describe this as technological determinism, but we think of it as navigating with a kind of techno-humanist compass. A compass helps us to choose a course of action, but unlike a blueprint or some immutable manifesto, it's dynamic rather than determinative. It helps us orient, reorient, and find our way.

It's also crucial that this compass be explicitly humanist, because ultimately every major technological innovation impacts human agency—our ability to make choices and exert influence on our lives. A techno-humanist compass actively aims to point us toward paths in which the technologies we create broadly augment and amplify individual and collective agency.

With AI, this orientation is especially important. Because what happens to human agency when these systems and devices, often described as agents themselves, do become capable of replacing us entirely? Shouldn't we slow down that eventuality as much as possible? A techno-humanist perspective sees it the other way around: our sense of urgency needs to match the current speed of change. We can only succeed in prioritizing human agency by actively participating in how these technologies are defined and developed.

First and foremost, that means pursuing a future where billions of people around the world get equitable, hands-on access to experiment with these technologies themselves, in ways of their own choosing. It also means pursuing a future where the growing capabilities of AI help us reduce the threats of nuclear war, climate change, pandemics, resource depletion, and more.

In addition, it means pursuing this future even though we know we won't be able to predict or control every development or consequence that awaits us. No one can presume to know the exact final destination of the journey we're on or the specific contours of the terrain that exists there. The future isn't something that experts and regulators can meticulously design—it's something that society explores and discovers collectively. That's why it makes the most sense to learn as we go and to use our techno-humanist compass to course-correct along the way. In a nutshell, that's "iterative deployment," the term that OpenAI, ChatGPT's developer, uses to describe its own method in bringing its products into the world. It's a concept my coauthor, Greg Beato, and I will explore and emphasize throughout this book.

As a longtime founder and investor in technology companies, my perspective is inevitably shaped by the technology-driven progress and positive outcomes I've participated in over the course of my career. I was a founding board member at PayPal and part of its executive team when eBay purchased it in 2002. I cofounded LinkedIn and have sat on Microsoft's board since 2017, following its purchase of LinkedIn.

I was also one of the first philanthropic supporters of OpenAI when it launched as a nonprofit research lab in 2015. I led the first round of investment in 2019 when OpenAI established a for-profit limited partnership in order to support its ongoing development efforts. I served on its board from 2019 to early 2023. Along with Mustafa Suleyman, who cofounded DeepMind, I cofounded a public benefit corporation called Inflection AI in 2022 that has developed its own conversational agent, Pi. In my role at the venture capital firm Greylock, I've invested in other AI companies. On my podcast Possible (Apple Podcasts | Spotify), I regularly talk with a wide range of innovators about the impacts AI will have on their fields—with a techno-humanist compass guiding our conversations. I also provide philanthropic support to Stanford University's Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) and to the Alan Turing Institute, the United Kingdom's national institute for data science and artificial intelligence.

I recognize that some might say such qualifications actually disqualify my perspective on AI. That my optimism is merely hype. That my idealism about how we might use AI to create broad new benefits for society is just an effort to generate economic return for myself. That my roles as founder, investor, advisor, and philanthropic supporter of many AI-focused companies and institutions create an ongoing incentive for me to overpromote the upsides and downplay the dangers and downsides.

I argue that the opposite is true: I'm deeply involved in this technology and I want to see it succeed exactly because I believe it can have profoundly positive impacts on humanity. My engagement in this domain has meant that I've seen firsthand the progress being made. That has strengthened my commitment, and thus I've continued to invest in and support a widening range of companies and organizations. I stay alert to potential dangers and downsides, and am ready to adapt, if necessary, precisely because I want this technology to succeed in ways that broadly benefit society.

One reason iterative deployment makes so much sense in the case of pioneering technologies like AI is that it favors flexibility over some grand master plan. It makes it easier to change pace, direction, and even strategy when new evidence signals the need for that.

Meanwhile, here we are presenting our argument to you in a book.

Roughly 2,400 years ago, Socrates critiqued the written word for its lack of dynamism in Plato's Phaedrus and for the way it made knowledge accessible to anyone:

You know, Phaedrus, writing shares a strange feature with painting. The offsprings of painting stand there as if they are alive, but if anyone asks them anything, they remain most solemnly silent. The same is true of written words. You'd think they were speaking as if they had some understanding, but if you question anything that has been said because you want to learn more, it continues to signify just that very same thing forever. When it has once been written down, every discourse rolls about everywhere, reaching indiscriminately those with understanding no less than those who have no business with it, and it doesn't know to whom it should speak and to whom it should not.

For Socrates, apparently, fixing his thoughts into written text represented a loss of agency. Had he turned his teachings into books himself, or rather scrolls, the reigning technology of his day, he would not have been able to control who read them. He would not have always been on hand to provide updates on his thinking, elaborate on nuances in the text, or correct misreadings. Consequently, face-to-face dialogic inquiry was his preferred technology for transmitting ideas.

But clearly generations of authors and readers thought differently. Why? Because ultimately written works increased the agency of authors and readers, enabling the latter to engage with, learn from, modify, expand upon, and, yes, perhaps even misinterpret or appropriate ideas from authors with which they might never have otherwise crossed paths.

As printing technologies improved, books evolved into a transformative global resource. Rolling about everywhere, indiscriminately reaching everyone, they functioned as early mobility machines, decoupling human cognition from human brains, democratizing knowledge, accelerating human progress, and providing a way for individuals and whole societies to benefit from the most profound and impactful human insights and innovations across time and space.

Of course, there are myriad other ways to share information now, and we'll be using many of them to convey the ideas in Superagency too. Along with the usual podcasts and social media, we'll be experimenting with AI-generated video, audio, and music to augment and amplify the key themes we're exploring here. To see how, check our website Superagency.ai.

But we're starting with a book—in part as homage to the essential truth that technologies that often seem decidedly flawed and even dehumanizing at first usually end up being exactly the opposite.

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt! Pick up a copy of Superagency at your favorite bookstore, and don’t forget to tune into my conversation with Reid this Thursday January 30th on the Next Big Idea podcast (Apple Podcasts | Spotify).

What positive impacts do you think AI could have in the next decade? Here are the categories of innovation I am most excited about (this is Rufus posting):

- improvements to global health

- improved learning for people of all ages around the world

- ever cheaper renewal energy, would could make possible carbon capture, better recycling, large scale water desalination, and any number of other benefits we have not considered

Finally, I share with Reid a general optimism around the impact of AI assistants, which could help increase our individual and collective IQ and EQ, increasing our humanity, if we do it right.

Don't get me wrong, I have some very serious concerns about the long term dangerous of unchecked, ever more powerful AI. But I agree with Reid's assessment we could be surprised to the upside in the next decade.

(Check out the Next Big Idea podcast on Thursday for our full conversation — https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-next-big-idea/id1482067226.)