The Dirtbag Billionaire Who Gave It All Away

A new book tells the story of Patagonia's founder and how he's rewriting the rules of business

Listen now on Spotify or Apple Podcasts:

What if the best way to win in business is to do the exact opposite of what everyone else is doing? While most CEOs chase growth at all costs, Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, chose a different path. Starting out as a rock climber and adventurer, when he pivoted to business he built products to last, created a company culture where surfing sometimes mattered more than spreadsheets, and even risked profits to protect the planet. Then, in a move almost unheard of in corporate America, he gave the entire company away.

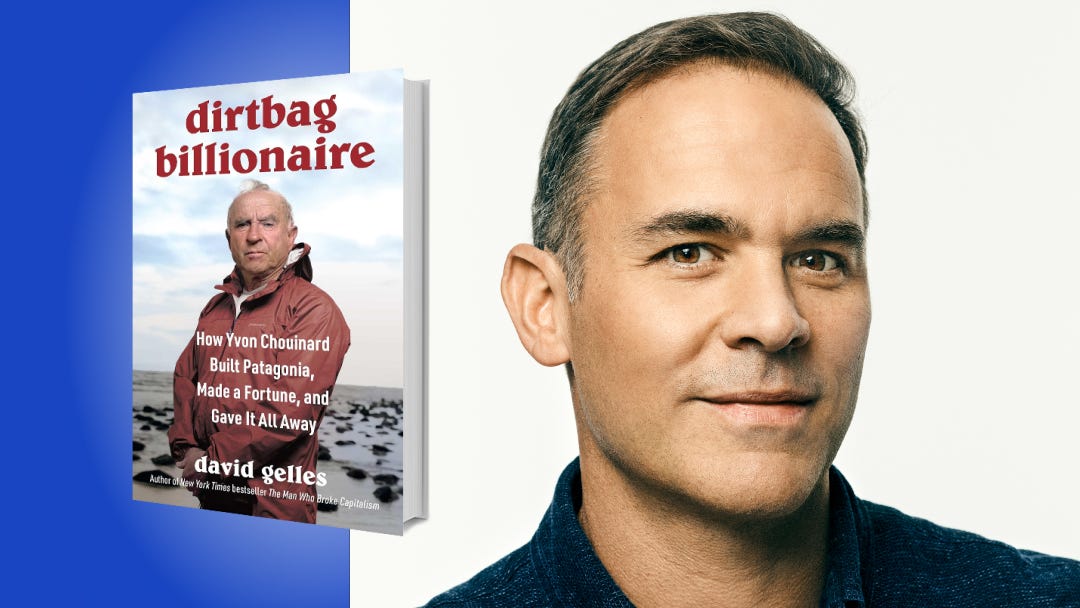

In his new book Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away, New York Times journalist David Gelles tells the story of how a reluctant businessman reshaped capitalism—and shows us what it looks like to build a company that puts people and the planet first.

Grab a copy on Amazon or read on for five of David’s key insights.

1. Quality matters.

When Chouinard was a boy, his father—a jack-of-all-trades handyman—taught him the importance of quality. If you buy a tool, his father said, buy the best one you can afford. That way you’ll have it for life, instead of wasting money replacing cheap tools that keep breaking. Chouinard took that lesson to heart. Everything he made at Patagonia was built to last, and over time he came to see that quality meant more than durability. It also included the materials used, the environmental impact of production, and the working conditions in the factories.

“If you buy a tool, his father said, buy the best one you can afford.”

Patagonia didn’t always succeed—there were plenty of products that flopped and fabrics that underperformed—but its holistic understanding of quality has been a central part of the company’s enduring success.

2. Create the world you want.

From the moment that Chouinard started Patagonia, he made it the kind of company that he himself would want to work for. He hired friends, built an environment where people could bring their full selves to work, and famously allowed employees to leave their desks and go surfing when the waves were good in Ventura, California. Patagonia also stood out for its support of women at work. It was one of the first companies to offer on-site childcare, and it still provides stipends that allow nursing mothers to bring a companion on business trips to care for their infants.

“From the moment he started Patagonia, he made it the kind of company he himself would want to work for.”

Chouinard carried this same philosophy into his philanthropy, funding projects that reflected the kind of world he wanted to live in. He bought up vast tracts of land in South America to help create new national parks, and he poured money into grassroots environmental groups—the kinds of small, scrappy activists fighting dams, mines, and deforestation. In both business and philanthropy, his goal was to build systems that embodied the values he believed in.

This week, Book of the Day is brought to you by Jim Ferrell, bestselling author behind the original classic Leadership and Self-Deception. His groundbreaking new book, You and We, is the essential connectivity playbook for leaders and changemakers navigating the age of AI, division, and polarization. Order your copy today.

3. Credentials don't really matter.

Chouinard was never much of a student. At one point in grade school he was getting straight D’s, and he never graduated from college. Instead, his education came from the outdoors: long climbing expeditions where he refined his gear, and backcountry trips where he tested Patagonia’s clothing. He called it his MBA—“management by absence.” Many of Patagonia’s leaders came from similarly unconventional backgrounds. One longtime CEO started out as an intern packing boxes in the warehouse and ended up running the company for two decades, learning on the job as she went. In the few cases where Patagonia brought in seasoned executives from outside, the culture almost always rejected them. For Patagonia, credentials mattered less than instincts, the ability to build trust, and plain old hustle.

4. Money isn't everything.

Early in his career, Chouinard had a revelation: the steel climbing spikes he was making—his company’s primary source of revenue—were damaging the rock faces he and his friends loved. He couldn’t accept that. Overnight, he stopped making them, jeopardizing the entire business, until he and others invented new alternatives that protected the rock. A few decades later, the company faced a similar crisis. Patagonia discovered that the cotton it was using was full of formaldehyde and other toxic chemicals that were making workers sick. Chouinard decided to stop using conventional cotton entirely and switch to organic—even though the supply chain didn’t yet exist and profits would take a hit. Over time, Patagonia helped create that organic cotton market, but it took years of financial sacrifice.

“He donated the entirety of Patagonia’s equity, setting up a situation where all future profits would support environmental causes.”

Finally, in perhaps his boldest act, Chouinard gave away Patagonia itself. He donated the entirety of Patagonia’s equity, setting up a situation where all future profits would support environmental causes. No IPO, no big payout, no family windfall—just a simple declaration that “Earth is now our only shareholder.”

5. Contradictions are okay.

Chouinard and Patagonia are far from perfect. As a boss, he could be mercurial—micromanaging at times, aloof at others—and he churned through executives, often changing his mind and sowing chaos. Patagonia, for its part, sells clothing that people don’t strictly need, relies on fossil fuels, and uses materials that contribute to the very climate crisis it campaigns against. Its gear is celebrated by elite athletes but mostly bought by city dwellers. These contradictions drive Patagonia’s leaders crazy, but they also fuel its restless push for improvement. The company doesn’t shy away from its hypocrisies; it wrestles with them, critiques itself, and tries to do better. That willingness to admit imperfection—and to keep striving anyway—has been as central to its identity as its environmental activism or high-quality gear. In a corporate landscape where self-criticism is rare, Patagonia’s contradictions have become a surprising source of strength.