The Science Behind Your Need to Please: Understanding the Fawn Response

How people-pleasing emerges as a trauma response, why it's not your fault, and the path to authentic self-expression

Listen now on Apple Podcasts or Spotify:

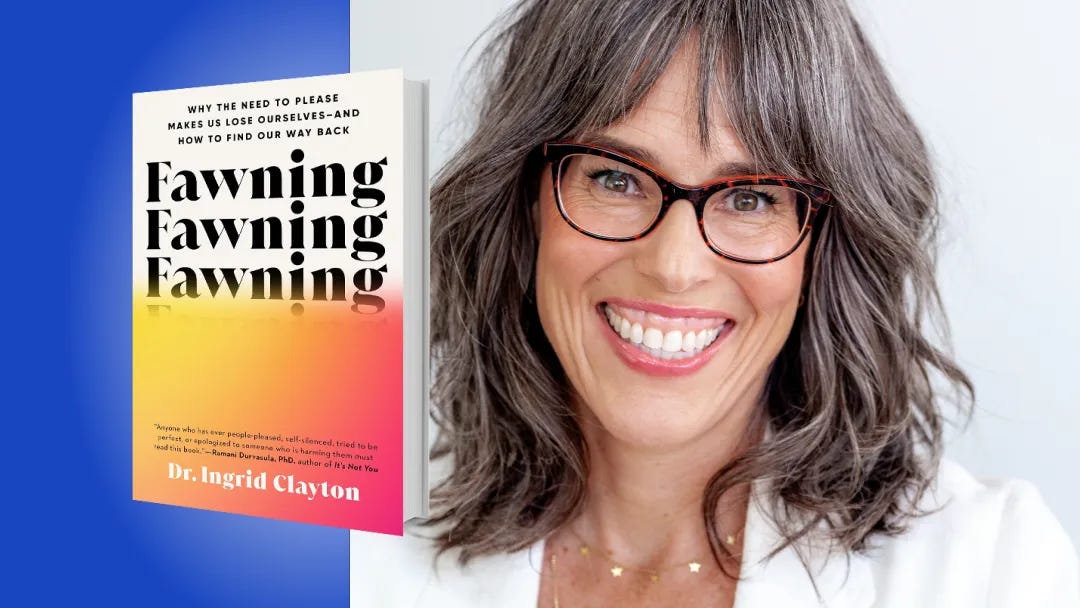

If you've ever been called a "people pleaser" or found yourself constantly putting others' needs before your own, what you're experiencing may actually be a trauma response called fawning. In the new book Fawning: Why the Need to Please Makes Us Lose Ourselves--and How to Find Our Way Back, clinical psychologist Dr. Ingrid Clayton explains this often overlooked alternative to fight-flight-freeze, an effort to appease threats by trying to make oneself more appealing. Whether in relationships, work, or family dynamics, understanding this pattern can help you reclaim your voice and authentic self. You can get Ingrid’s book on Amazon and check out five key insights below:

1. The trauma response alternative to fight or flight.

Sometimes we have trauma in our lives but don’t recognize it as such, especially when it comes to complex trauma. Unlike more commonly understood forms of trauma, like a car crash or a natural disaster, complex trauma is prolonged and ongoing. It doesn’t come from a single, clear event, but rather from persistent threats to our safety and sense of self or what’s possible in our vital relationships. It’s often rooted in childhood or relational experiences: growing up with an alcoholic parent, enduring emotional neglect, facing chronic poverty, or racism. These are not one-time shocks, but slow-drip injuries to the nervous system and spirit.

In these situations, the typical trauma responses we think of—fight, flight, or freeze—often aren’t options. You can’t fight your parent or flee from your family at age six. And freezing only goes so far. That’s when the nervous system may turn to fawning.

Fawning means trying to stay safe by becoming more appealing to the person who makes you feel unsafe. You try to appease, please, and avoid conflict at all costs. Fawning can look like:

Smiling and laughing off an aggressive advance you don’t want.

Staying silent about your values in a toxic workplace to avoid losing your job.

Rationalizing a parent’s abusive behavior to preserve the relationship.

For me, growing up with a narcissistic stepfather, I learned to fawn early and often. But I didn’t have the language for it until I became a trauma therapist and discovered the term “fawning,” coined by psychotherapist Pete Walker. Suddenly, everything I’d struggled with for decades made sense.

Despite being sober since I was 21, reading every self-help book I could find, sitting on various therapists’ couches, and getting three degrees in psychology myself, I was stuck in a chronic fawn response. My dysfunctional relationships, my inability to set boundaries, my silenced voice—all of it traced back to this survival strategy. Naming it was the beginning of reclaiming myself.

2. People pleasing is a survival strategy, not a personality flaw.

People-pleasing and codependency are different symptoms of a chronic fawn response. These patterns often served a purpose in childhood. They helped you secure the love, safety, or connection you were dependent on. In that context, they were brilliant adaptive protectors. The body did what it needed to survive and reflexively responded in a nanosecond, without your conscious consent.

“Naming it was the beginning of reclaiming myself.”

The challenge is, we often carry these same responses into adulthood when they no longer serve us. Because they’re so deeply wired into our development, we often can’t see where we end, and fawning begins. We may think we’re just being nice or helpful, not realizing that we’re sacrificing our own authenticity.

People-pleasing often gets painted as a manipulative or submissive trait, but it’s about safety. If you learned that keeping others happy was the only way to avoid danger or abandonment, of course you kept doing it. The problem is, when you’re always attuned to what others want or need, you lose touch with yourself. You abandon you.

This week, Book of the Day is brought to you by two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and Harvard Professor of Psychology Steven Pinker. In his newest book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows…, Steven invites us to understand the ways we try to get into each other’s heads and the harmonies, hypocrisies, and outrages that result. Pick up your copy today.

3. Fawning requires self-abandonment.

To survive your childhood, the various hierarchies of your life, you had to become who you needed to be—not who you truly were. That meant detaching from your inner world: instincts, intuition, insights, personality. You learned to shape-shift, edit yourself, and silence what was real in order to stay safe, loved, or simply tolerated.

The work of unfawning is the work of coming home to yourself. It means learning to go inward and listen to your own voice—your needs, your preferences, your truth—and starting to believe it matters. It means checking in with you first, before constantly attuning yourself to the moods, wants, or expectations of everyone else. This isn’t easy. It doesn’t happen overnight. But the gift of unfawning is finally starting to live a life that feels like yours.

“It means checking in with you first, before constantly attuning yourself to the moods, wants, or expectations of everyone else.”

I’ve seen this unfold time and again. I’ve had clients change careers entirely as they reconnect with their inner voice. I’ve seen people leave abusive relationships, not out of anger, but clarity. They begin to really see themselves for the first time. And they begin to seek alignment with who they truly are in their friendships, career goals, and even hobbies. Unfawning isn’t about being selfish. It’s about being real.

4. Unfawning doesn’t mean you’ll never fawn again.

Fawning may still feel like the safest option in some situations, and that’s ok. The goal isn’t total elimination. Rather, it’s creating more capacity, flexibility, and choice. Fawning should not be default mode. When you’re not trapped in it anymore, you can better assess and decide if fawning is the only (or best) way through a particular situation.

This work invites us to step out of an all-or-nothing mindset. We’re not aiming to go from broken to healed, or from unsafe to always safe. That’s not realistic. Unfawning is about:

Growing your capacity for new emotional and relational territory.

Learning to hold discomfort and risk vulnerability.

Explore new ways of being.

It will feel scary. The nervous system will likely still equate discomfort with danger. But part of this work is learning to distinguish between the two. You’re forging a new path that may not have been modeled for you or ever felt possible. But with each step—each boundary set, each moment of truth spoken—you strengthen the muscles of self-trust.

5. Fawning is not your fault.

We live in a world that often requires fawning. From rigid, hierarchical work environments to patriarchal systems and racial inequity, many of us learned early on that being agreeable, accommodating, and non-threatening keeps us safe.

In systems that don’t recognize or value your full humanity, fawning isn’t weakness—it’s wisdom and adaptation. When we understand that, we can start seeing our behaviors with more compassion. We can stop blaming ourselves for doing what we had to do. And we can recognize the double binds we’re often placed in, where there is no good option or clear way out.

Our work is to grow beyond rigid coping, to move out of childhood patterns and into the rest of life—not by erasing what protected us, but by honoring it and then slowly moving into more internal safety. This isn’t a linear path, and there is no final destination. This is a lifelong journey of returning to yourself, again and again.

I used to be a people pleaser! It took me some time to accept it and cultivate self respect. Even If I don’t anymore I can still catch myself to day yes when I want to say no. I am not afraid to change my mind anymore.

I'm pretty sure the word 'fawning' wasn't coined by psychotherapist Pete Walker! he might have given the existing word a more technical meaning, perhaps.