Who Designed Design?

Once just a word, now a worldview—how a 20th-century invention came to shape everything from your phone to your future.

Listen now on Substack or Apple Podcasts:

Have you ever noticed that some spaces and objects feel pleasing and easy to use -- and some just…don’t? The difference is design. And while we don’t always think about it, design shapes nearly everything we interact with—from the way we fill out forms to how we furnish our homes to how we move around the cities we live in.

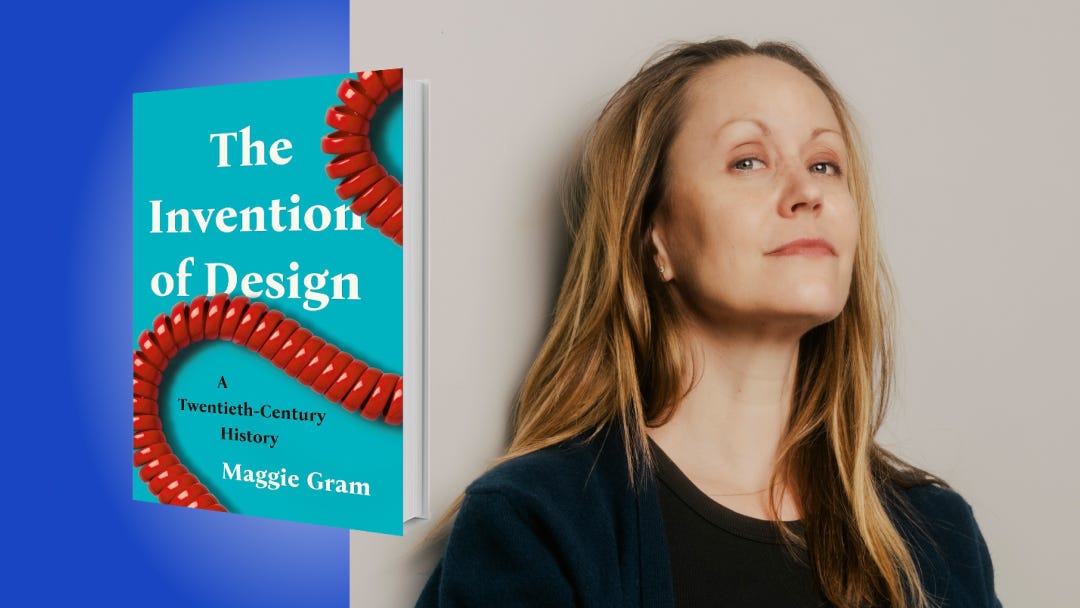

In her new book The Invention of Design: A Twentieth-Century History, Google experience designer and cultural historian Maggie Gram takes a fresh look at where the concept of design actually came from, how it became a tool for progress—and how, sometimes, it’s used in ways that do more harm than good.

1. The idea of “design” can seem timeless, but it’s a pretty recent invention.

What do you think of when you hear the word “design?” Most people will probably think of something rather general and nonspecific, like when thinking of the word “art,” “power,” “love,” or “dream.” Like these ideas, the idea of “design” can seem timeless or universal. But it’s actually a pretty recent invention.

Before the 20th century, people didn’t see aesthetics, function, and problem-solving as related. Over the 20th century, they came to see all of these (as well as human-centeredness, experience, and even thinking itself) as parts of one thing: “design.” The idea of design was developed over the period from approximately 1890 to about 2010. People invented it as a concept, gradually and inadvertently, and then invested faith, hope, and capital in it.

2. There’s a reason design was invented in the 20th century.

By the 1890s, the Industrial Revolution had transformed Great Britain, most of Europe, and the United States from agrarian and handicraft economies into machine-driven industrial ones. Soon, barely regulated markets would dominate everyday life, uprooting people and polluting rivers and degrading working conditions.

“Before the 20th century, people didn’t see aesthetics, function, and problem-solving as related.”

The idea of “design,” whether it meant making things more beautiful, more human-centered, or more useful, helped make living under and participating in capitalism feel less brutal and more friendly and creative. Artists who entered industry over the course of the 20th century—Eva Zeisel, Leo Lionni, Walter Teague, Ray Eames, and countless others—became not everyday workers but “designers.” Their work was seen as not just profitable but also generative, creative, and valuable to civic life.

This week, Book of the Day is brought to you by sales strategist Rob Langejans, founder of AlwaysStrategic and author of Representing Products. In a world where B2B product presentations all sound the same, Langejans offers a fresh, research-driven approach to help your team break through the blur. Using the ReP Method™, this book teaches you how to reach the buyer’s brain, reveal true product value, and relate with authentic presence—especially in high-stakes, competitive deals. If your presentations are blending in, this book shows you how to make them count. Get your copy today.

3. Today, the idea of design is everywhere, and we value it highly.

We read magazines like Wallpaper* (which is distributed from Montreal to New Zealand to Hong Kong) and Dwell (which not only writes about but builds prefab houses). We listen to the radio show 99% Invisible. We buy things from a Target line called “Made by Design.” When we’re feeling flush, we wander through the showrooms of “Design within Reach.” Cities from Los Angeles to Helsinki have hired Chief Design Officers. Universities pay consultants to help them implement “design thinking.” It is what we might call a design-y time.

4. Design doesn’t automatically make things better or more just.

As the critic Nikil Saval has written, “design is an inherently futurist medium.” To believe in design is to believe that human society can change for the better. This aspect is why design is particularly fetishized in Silicon Valley—that techno-utopian wonderland, with its obsessions with the new, improvement, enhancement, and optimization.

“To believe in design is to believe that human society can change for the better.”

Silicon Valley’s obsession with design has manifested in private spaceflight, Tesla cybertrucks, and a collective fixation on artificial general intelligence. But these are examples of how not all change, and indeed not all design, is inherently good. We ought to be wary of the uncritical fetishization of anything, not least design itself.

5. Despite that caution, design can be a good tool.

Just imagining and believing and “ideating,” as we say in my field of experience design, isn’t enough. Actually making things, doing things, and transforming political arrangements are necessary if we’re going to make contemporary life genuinely better and more just for more people.

The designer Sylvia Harris redesigned the U.S. Census to drive higher participation rates in Black, Latinx, and Native American neighborhoods. The U.S. Census helps determine who the U.S. government funds; the federal government relies on census data to allocate approximately $1.5 trillion across hundreds of federal programs. Redesigning the census makes a real and material difference. Design can chip away at wicked problems, and it should.

Mark your calendar and submit your questions for a Q&A with medical researcher Eric Topol about his latest book, Super Agers: An Evidence-Based Approach to Longevity. The Q&A will be hosted by NBIC's Editorial Director Panio Gianopoulos, and will be available for you to join live on July 16th at 12pm ET.

Upgrade to a paid subscription to RSVP: