How to Become an Emotional Ninja

An exclusive excerpt from Shift: Managing Your Emotions — So They Don’t Manage You by Ethan Kross.

I think of Ethan Kross as a new friend, and a compelling thinker — he’s an experimental psychologist, neuroscientist, and director of the Emotion and Self-Control Lab at the University of Michigan. I met him when we had him on the show to talk about his first book, Chatter: The Voice in Our Head. Tomorrow, his second book, Shift: Managing Your Emotions — So They Don’t Manage You, will be published. We are sharing something today that I think you will enjoy — an exclusive excerpt from Shift.

In the early pages, Ethan refers to our emotions as our “Stradivarius,” which is to say a beautifully crafted violin that makes exquisite music. We are often, of course, at the mercy of our emotions. They can be discordant. But there are techniques we can learn to control them, techniques outlined in Shift. If we don’t learn to play our emotional Stradivarius — learn to shift between the notes with intention — “it runs the risk of playing us.”

Listen to my conversation with Ethan on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, enjoy the excerpt, and share your thoughts in the comments below.

—Rufus

In the mid 1860s, an American diplomat traveling in Peru came across a remarkable artifact. Ephraim George Squier — also an archaeologist — paid a visit to a socialite who collected ancient artifacts. She welcomed Squier into her home and allowed him to inspect her Incan treasures. After admiring the myriad stone figures, sculptures, and other items she had accumulated, he noticed a peculiar specimen: a skull fragment that had been unearthed from an Incan cemetery.

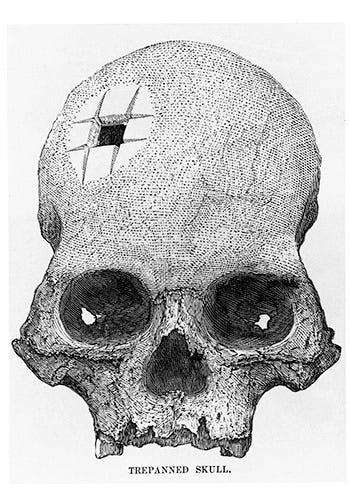

Ancient skulls are common archaeological finds, but this was no ordinary relic. A nearly symmetrical half-inch square with clean edges had been carved out of the frontal bone, the area of the skull that sits above the eyes and encases the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain that enables us to plan, manage our lives, and reason logically. Plenty of ancient skulls had, of course, been unearthed with damage, but usually that breakage was irregularly shaped and most likely the consequence of a traumatic event or prolonged exposure to the elements. The four surgically precise incisions on this Incan skull told a different story.

Squier sent the skull across the Atlantic to be examined by the famous French surgeon Dr. Paul Broca, one of the world’s foremost experts on ancient human skulls. After inspecting the cranium, Broca concluded that the square-shaped hole represented clear evidence of a surgical intervention that predated the European conquest of the region in the sixteenth century and was performed on the deceased person while they were still alive.

The hole carved into the Incan skull resulted from a procedure that is now widely considered one of the first surgical techniques developed in human history: trepanation, or the creation of holes in people’s skulls. That our distant ancestors were capable of carefully trepanning people’s skulls is remarkable. But even more incredible is one of the reasons why they are believed to have used this intervention: to help people manage their emotions.

Consider that for a moment: One of the earliest forms of surgery in the history of medicine was used to help people regulate their feelings.

It is impossible to know exactly which emotional maladies warranted receiving a hole in the head thousands of years ago. Historians suspect the technique was likely used to help people manage extreme cases of depression, mania, and other conditions characterized by emotion dysregulation. Regardless, what we can say for certain is that carving a hole in a person’s head to provide them with emotional relief was not a great idea. But when you look at the history of how our species has dealt with emotions since those early days of head carving, you see that the struggle has always been real. And for as long as we’ve been grappling with our emotions, we’ve been trying to find tools to regulate them.

Leeches.

Exorcisms.

Witch burnings.

We’ve come up with remarkably creative (and cruel) measures to control our emotions. In the seventeenth century, pressing a burning iron rod to the skull was a recommended solution for managing heartbreak, while centuries later mineral water was pedaled as a stress tonic. And as shocking as the treatment may seem to us today, the spirit of trepanation lived on until only a few decades ago in the form of the lobotomy, in which a surgeon would flip open the eyelid, slip an ice-pick-shaped instrument through a person’s eye socket, and poke around in their frontal cortex to sever key neural connections. In fact, António Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurologist, shared the Nobel Prize in 1949 for developing the procedure to treat extreme emotional states. The structure of DNA, the discovery of insulin, the development of MRI technology — Moniz’s procedure reached the same level of distinction as these extraordinary discoveries. We human beings have considered emotions so perplexing — so destructive — that we have resorted to carving holes in our heads, ingesting heavy metals, and disabling parts of our brains just to get some relief.

And — like our ancient forebears — we remain in trouble in the emotion department.

College campuses are overrun with students who require extra support to help with their emotions. Britain and Japan have ministers of loneliness, while the U.S. surgeon general has made combating social isolation a national crusade. Corporations invest millions in programs to address burnout. Even “the Boss” Bruce Springsteen himself has talked about his struggles with depression. We install apps on our phones to keep our stress levels in check. We spend money we don’t have in a wellness industry that promises to make us just a little bit happier. A 2020 report found that approximately one in eight adults in America took an antidepressant every day to manage their emotions. A medication that, although genuinely helpful for many people, is far from a panacea.

More than half a billion people worldwide suffer from some form of depression and anxiety, afflictions that cost the global economy a staggering one trillion dollars a year.

Interventions have undoubtedly improved since the days of leeches and lobotomies. Our methods have become much subtler — and less damaging. Advances in talk therapy, innovations in psychopharmacology, and the blending of ancient and modern contemplative traditions have expanded our access to relief from emotional distress. And yet despite all these efforts, the statistics on mental health and well-being are going in the wrong direction and keep getting worse. More than half a billion people worldwide suffer from some form of depression and anxiety, afflictions that cost the global economy a staggering one trillion dollars a year.

One trillion dollars.

Patchwork solutions reside in myriad places, from the bowels of the internet to the dusty shelves of the library. As a result, many of us resort to cobbling together coping tactics that range from kind of effective to actually harmful without really understanding how they all fit together to help us (or not). A little meditation here, a cold plunge there, some cognitive restructuring, maybe a cocktail or five to smooth things out.

Meanwhile, people who are good at managing their emotions are less lonely, maintain more fulfilling social relationships, and are more satisfied with their lives. They experience fewer financial hardships, commit fewer crimes, and perform better at school and work. And they’re physically healthier as well: they move faster, look more youthful in photographs, biologically age less quickly, and live longer. Simply put, the ability to control your emotions isn’t just about avoiding the dark side of life; it’s about enriching the positive, generative, and rewarding dimensions of existence as well.

The question we now face is the same one that likely inspired our ancestors to drill holes in their heads: What do we do about all these feelings?

***

In 2021, I published my first book, Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It. Its central question: Why do our attempts to work through our negative feelings often backfire, leading us to feel worse, and what does science teach us about how to harness our capacity for self-reflection?

Immediately after publishing the book, I set off on an extended book tour that lasted about two years. After events, people would come up to me wanting to talk. They were grateful for the book and had feedback about how it helped them, which was wonderful to hear. But they had questions — lots of them — about the broader terrain of emotions and how to manage them:

Should I always be in the moment?

Can you really control emotions?

Why do I struggle to do the things I know I should do in the heat of the moment?

It was as though I had just taught them about heart disease, which was great, but they also needed help dealing with inflammation, diabetes, and cancer.

I wrote this book to provide you with a blueprint for understanding your emotions — what they are, why they matter, and how to harness them.

People talked about having parents and bosses who brushed their feelings aside. They struggled to define what an emotion was and asked me why they never learned about how to manage them growing up. I am not exaggerating when I say that some people would come up to me with these questions in tears. And it was everybody: elite athletes, CEOs, parents of teenagers, special forces operators, you name it.

What became clear to me during those moments was how curious people were about their emotional lives and how motivated they were to manage them. Which is why I decided to write this book. To provide you with a blueprint for understanding your emotions — what they are, why they matter, and how to harness them.

Our emotions, both the positive and the negative ones, are tools we use to navigate the world. They influence who we fall in love with and who we hate. They motivate us to stay longer hours at work to realize our dreams and rein in our aspirations when they no longer serve us. They can fill our lives with health and vitality or sap our energy when we lose sight of what matters. And they are often the difference maker when it comes to sustaining close bonds with others or becoming mired in relationships fraught with conflict. And yet, for all their profound impact on our lives, few of us receive a science-based guide for how to turn the volume on our emotions up or down, or how to transition gracefully from one emotional state into another.

Over the past twenty years, we have witnessed a scientific renaissance in our understanding of these mechanics of emotions — the psychological and neural “nuts and bolts” that explain how emotions work — and an explosion of new methods to measure and test those mechanics. Neuroscience techniques allow us to visualize where and how quickly different brain networks become activated when people experience and control their emotions. Smartphones and wearables enable us to observe people’s emotional responses unfold organically in real time as they navigate the world. Internet technologies permit us to run experiments on vast numbers of people scattered across the globe and gather unprecedented amounts of data.

These innovations, combined with our more traditional methods of experimentation, have transformed our way of thinking about emotions. We’ve learned, for example, that the key to emotional salvation doesn’t always involve living in the present, and that far from being toxic, negative emotions can sometimes help us in surprising ways.

And perhaps most important, we’ve discovered that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions to our emotional problems. Would you ever take your vehicle to the mechanic and expect them to fix it with one tool? Of course not! Cars are complex, dynamic machines that require different tools to manage different problems. The same concept applies to us. Our emotional needs change from situation to situation, person to person, and certainly day to day — even moment to moment. We need a wide range of tools to meet those needs. The great news: you already have them.

It starts with understanding what I call the major emotional “shifters” that we all have inside us. We can harness our senses to automatically shift our emotions. We can deploy our attention strategically in ways that help us conquer our greatest fears and savor our most joyous experiences. And we can alter our perspective on difficult circumstances to help us manage our most painful emotional states. These shifters help us move from one emotional state to another, allowing us to dampen or amplify feelings.

Each of these “internal shifters” can also be activated by forces outside us — the spaces we inhabit, the people we interact with, and the families, organizations, and cultural institutions we belong to. Understanding how these different “external shifters” affect us puts us in the position to make smart choices about how we interact with them to boost the power of the tools we have inside ourselves.

How and when to use these shifters, and which ones fit the job — that’s what the science behind my new book, Shift, will help you figure out. Think of it as an instruction manual for the operating system you already have but might not be using to its fullest potential.1

From the book SHIFT: Managing Your Emotions — So They Don’t Manage You by Ethan Kross, PhD. Copyright © 2025 by Ethan Kross, PhD. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Ethan,

Thank you for Shift and the wonderful conversation!

I am already employing techniques to regulate my emotions with greater intention.

Question — I am generally pretty good at emotional regulation, except when I am triggered by a comment from one of my loving children like, "doing the dishes is a parent's job."

I know I should rehearse in advance the kind of funny, loving responses I would like to offer in such moments ... but of course I often forget in practice.

Any thoughts on techniques?